On the Role of Human Development in the Arab Spring

This essay traces the impact of human development on political change, focusing on the events of the Arab Spring. Over the past generation, most Arab States experienced rapid progress in human development outcomes, including declining child mortality, increasing schooling and increasing height of women. I posit that improvements in human development laid the foundation for mobilization against political regimes. This thesis rests on three interlinked propositions. First, human development led to increased political participation and knowledge. Second, basic human development led to a dramatic increase in population needs and expectations, creating new policy challenges and reducing public dependency on regimes. Finally, the preceding changes resulted in values and attitudes conducive to regime change. Each proposition builds on new theories of human capital accumulation over the life course that isolate the human dimension of national development. I provide provisional support for these pathways through cross-regional comparison and evidence from the unique case of Egypt. I highlight the need for study design and datasets that can test causal pathways from health and education to political participation and attitudes.

Introduction

On December 17, 2010, in the provincial Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, a 26-year-old street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest his humiliation at the hands of corrupt local police, succumbing to his self-inflicted injuries January 4, 2011. Within weeks his act led to the end of the 23-year rule of Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. A wave of protests, uprisings, and insurrections commonly grouped under the term "Arab Spring" subsequently spread through much of the Arab world. As we move further away from those initial events, we can look beyond the precipitating causes and consider the forces underlying the revolutions. In December 2010, Population and Development Review published "Routes to Low Mortality in Poor Countries, Revisited," a paper highlighting the quiet but exceptional achievements of Arab nations in reducing mortality (Kuhn 2010). Mortality reductions coincided with comparable shifts in early childhood morbidity, nutrition, schooling, and other dimensions of human capability (Tabutin and Schoumaker 2005). This paper explores the theoretical logic and quantitative evidence linking human capability expansion to political mobilization.

At least since the storming of the Bastille in 1789, debate has raged over the socioeconomic antecedents of revolution (Komlos 2003). The more widely acknowledged framework is the Malthusian "let them eat cake" model, in which widespread deprivation drives revolution (Schubert and Koch 2011). The bourgeois model, first articulated by Condorcet and elaborated by Marx, Habermas, and others, argues instead that improved living standards allow populations, particularly emerging middle classes, to engage in political change activities, whether revolutionary or otherwise (Habermas 1970; Boswell and Dixon 1993). Today's recessionary climate supports a neo-Malthusian inclination, and so leading explanations for the Arab Spring have related to food insecurity, unemployment, and frustrated youth.

Nevertheless, development theory and practice remain shaped by the hoped-for connections between individual well-being and broader societal change (Thornton 2001). New theories of life course human capital accumulation have isolated the human dimension of national development, with particular emphasis on economic growth (Fogel 1993). Yet many studies find the growth impacts of human capital to be modest in the absence of effective institutions and governance (Acemoglu and Johnson 2007). The pathway from human capital to political change, if it exists, is both important in its own right and for helping us understand the pathway to economic growth.

In this essay I argue that improvements in human development laid the foundation for popular mobilization again political regimes in the Arab world. This thesis rests on three interlinked propositions. First is the uncontroversial yet undertheorized proposition that human development increased political participation and engagement. Second, human development drove a dramatic increase in population needs and expectations, creating new policy challenges and reducing public dependency on regimes. Such shifts were not merely aspirational, but resulted from a nexus of changing physiology and social environment as well as aspiration. Finally, the preceding changes led to the emergence of popular values and attitudes conducive to regime change. I begin by revisiting the modernization approach to social and political development.

From modernization to human development

The contemporary approach to development and political change emerges from modernization theory. Seymour Lipset highlighted the role of four indicators of economic development—wealth, industrialization, urbanization, and education—in the emergence of democratic governance (Lipset 1959; Lerner 1958). Even at this early date, Lipset argued that education increased the individual capacity to engage in political action and democracy:

- Education presumably broadens men's outlooks, enables them to understand the need for norms of tolerance, restrains them from adhering to extremist and monistic doctrines, and increases their capacity to make rational electoral choices (Lipset 1959: 78).

Lipset's framework treated democratic transition and regime stability as indistinguishable concepts, thus ignoring both the relationship between modernization and revolution and the possibility of democratic revolutions of the sort that occurred in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s. In the 1960s Samuel Huntington clarified the relationship between modernization and revolution, noting that modernization, including urbanization and rising literacy, could lead to rising and unmet expectations, popular frustration, and violent revolution in societies lacking strong political institutions (Huntington 1968). As a conservative and a Malthusian, Huntington cautioned policymakers against promoting too rapid modernization.

Though many mentioned the role of education and literacy, empirical studies in the modernization tradition continued to focus primarily on general relationships among indicators of economic or industrial change and democracy (Moore 1966; Przeworski and Limongi 1997). Yet as a simple aggregate relationship, the modernization-revolution argument is undermined by the Malthusian counterargument that regime change results not from human improvement but from human misery and, conversely, that effective social and health interventions actually bolster the political standing of a regime. The provision of basic services may be especially important in establishing state legitimacy and popular assent, particularly for regimes that are autocratic or in transition (Reich 1995; McNicoll 2006; Glassman 2007). These motives were certainly present in Egypt, where the unelected government of President Hosni Mubarak and opposition groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood used health and welfare programs to support dueling claims to popular legitimacy (Al-Awadi 2004; Grynkewich 2008).

We can reconcile the modernization and Malthusian models by considering the temporal factors in the development process, which suggest that basic interventions may carry short-term benefits and long-term costs for regimes. Basic interventions are often self-limiting endeavors with diminishing impact over time. This shift is clearest in immunization programs, which may lead to herd immunity, but many other health interventions also yield enduring, irreversible success or foster alternate supply routes (Omran 1971). As basic needs are met, more complex and expensive needs often emerge. This shift is evident in the tendency for health expenditure to increase inexorably as a percentage of national income and in the broadening of development priorities in national and global discourse (Thornton 2001; Hughes et al. 2010). Recent studies address the role of increased social spending demands, fears of globalization, and perceptions of inequality in driving regime change in middle-income countries (Haggard and Kaufman 1997; Acemoglu and Robinson 2001; Rudra 2005).

What is less clear is whether the temporal path from basic progress to rising expectations is a direct causal product of improvements in human capability, an associated process driven by some broader development force (e.g., improving living standards), or a by-product of developmentalist thinking. A central assertion of this essay is that the broadening of development priorities is indeed a direct result of past human development progress. This causal relationship does not merely reflect rising aspirations, but also reflects specific physiological and social implications of the life course model of human development.

Human capital, development and transformation

A human development approach can improve our understanding of societal change by isolating the human contribution to productivity and prosperity from nonhuman inputs like finance and natural resources. Amartya Sen argues that the human development approach is especially important to understanding nonmarket activities occurring within the family or society.

It is important to take note also of the instrumental role of capability expansion in bringing about social change (going well beyond economic change). Indeed, the role of human beings even as instruments of change can go much beyond economic production and include social and political development. For example, expansion of female education may reduce gender inequality in intrafamily distribution and also help to reduce fertility rates as well as child mortality rates. Expansion of basic education may also improve the quality of public debates. (Sen 1993: 296).

In Sen's framework, human capabilities are both markers of past success and stocks of potential human agency (Sen 1990). Through aggregation over time, basic capabilities like schooling and health play a foundational role both in an individual's life course and in societal development. It is also now widely recognized that rising income is not a prerequisite for improving health, schooling, or other capabilities (Preston 1975; Caldwell 1986; Cutler et al. 2006). Efforts to maximize human capital at low cost have become the hallmarks of development agencies, including groups like the World Bank that once focused on the physical inputs to growth (Sachs 2001). Yet a deep understanding of the long-term benefits of these efforts is only just emerging.

The greatest progress in understanding human development over the life course has come in studies of health, nutrition, and physical well-being. Recent studies highlight the effect of phenotypic variation in physical function, resulting from both improved living standards and programmatic health interventions, on subsequent life course outcomes. David Barker's thrifty phenotype hypothesis posits that extreme nutritional deprivation early in life drives adaptations in organ function and metabolism that leave individuals less able to process glucose- or lipid-dense foods, thereby predisposing them to cardiovascular disease and diabetes (Barker 1998; Barker and Osmond 1986). While Barker‘s original formulation related to deprivation inside the womb, further investigation has demonstrated that this adverse programming continues throughout childhood (Godfrey and Barker 2000; Victora et al. 2008; Uauy et al. 2007). (1)

It is important to separate embodied capital, an individual's physiological capabilities, from forms of human capital like schooling. First, physical and cognitive changes typically precede improvements in schooling, both within the individual life course and within many national development strategies. Second, stunting carries implications for long-term physical and cognitive functioning that act both independently of and in concert with schooling. (2) A recent study by Barham (2011) uses large-scale, long-term evidence from a maternal and child health / family planning (MCH/FP) experiment conducted in the Matlab area of Bangladesh from 1977 to 1989 to identify a 0.4 standard deviation improvement in cognitive performance for children in the MCH/FP treatment compared to those in the comparison area. The study also observed a 0.3 SD gain in height. Educational impacts were somewhat smaller, only 0.25 SD, and cognitive benefits persisted in the presence of controls for education. Interactions between education and program exposure were not significant. While cognition is clearly related to schooling as both cause and effect, it also contains dimensions uniquely related to health. Third, improvements in physical strength and security drive increases in longevity and decreases in lifetime mortality risks, facilitating entirely new patterns of savings, human capital accumulation, and time allocation across the life course. This is most evident in the emergence in modern societies of an extended adolescence, a life stage that offers new opportunities for individual and collective advancement along with new policy burdens for the state (Kaplan 1997; Lloyd 2005).

These findings point to a powerful role of embodied capital in driving economic growth and precursors to growth such as schooling, employment, productivity, and wages (Grantham-McGregor et al. 2009). Robert Fogel's theory of ―technophysio evolution‖ outlines the parameters of this effect, using evidence of changing stature among US soldiers in the nineteenth century to argue that human nutrition is the thermodynamic engine for human productivity and investment (Fogel and Costa 1997). Fogel (1994) attributed one-third of the economic growth in England between 1790 and 1980 to improvements in health and nutrition. Arora (2001) attributed found comparable health impact in looking at a broader range of developed countries. In each of these historical studies, long-term growth also depended on well-functioning institutions, markets, and infrastructure, factors not obviously influenced by health.

More recent studies highlight the surprisingly limited aggregate growth returns to the post-WWII epidemiologic transition outside of a relatively small number of countries in East Asia and the European Union periphery (Acemoglu and Johnson 2007). Equilibrium models account for the direct impacts of health on labor market participation and second-order effects including increased schooling, savings rates, and foreign investment and declining fertility (Weil 2007; Hughes et al. 2010). These studies tend to find modest, non-negative impacts of health on likely future growth, but impacts are small relative to other drivers of GDP growth, and uncertainty is high. One key source of uncertainty in all models is the extent to which citizens can actually put their health to productive use given long-term institutional impediments.

In light of these results, it is surprising that so few studies have attempted to identify the relationship between human capital, particularly health, and political and institutional conditions that are important in their own right and as drivers of growth. No cross-country study to date has used improving health to predict political change, though a few Malthusian studies tie high infant mortality to the emergence of violent conflict and state failure (Goldstone et al. 2010). Studies of schooling and political change have yielded few definitive conclusions (Hannum and Buchmann 2005). Statistical power has been weak, particularly when health is used to predict revolution rather than gradual democratization (Goldstone et al. 2010). Problems of causality and unobserved heterogeneity persist (Castello-Climent 2008; Acemoglu and Johnson 2007).

There is thus a need for a structural model of the effects of human capability on political change that relates specific aspects of the individual life course and societal transition to specific precursors of popular uprising. In particular, we must separate increased political engagement from the desire for change. The events of the Arab Spring offer a unique opportunity to consider these effects, beginning with the sheer scale of improvements in human development outcomes.

Human capital improvement on the eve of the Arab Spring

Table 1 highlights the extraordinary pace of regional change from 1980 to 2010 in the key components of the Human Development Index (HDI) of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), comparing 17 core Arab states including the Palestinian Territories (henceforth referred to as "Arab States") to 23 from Latin America / the Caribbean ("Latin America"), 25 from Asia and the Pacific ("Asia"), and 46 from Sub-Saharan Africa ("Africa"). This presentation separately lists Egypt, the largest Arab nation by population and cultural influence and site of the most globally significant revolution to date. HDI for Arab States improved from 0.425 in 1980 to 0.630 in 2010, an annualized rate of about 1% gain per year that pushed the average Arab state from the 68th percentile of the national distribution to the 59th percentile. Only Asia showed more rapid improvement, and this advantage was driven largely by GDP growth, which contributes one-third of the HDI. Asia saw GDP growth of over 5% per year, compared to less than 1% for Arab States and Latin America, and close to 0% for Africa.

| Change in the Human Development Index and Components, 1980-2010, major developing regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Arab States | Egypt | Asia / Pacific | Latin America / Caribbean | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Human Development Index | |||||

| 1980 | 0.425 | 0.393 | 0.359 | 0.573 | 0.289 |

| 2010 | 0.630 | 0.620 | 0.588 | 0.704 | 0.388 |

| Annualized change | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.7% | 0.7% | 1.0% |

| Gross Domestic Product per capita (PPP adjusted) | |||||

| 1980 | 8,004 | 2,633 | 1,136 | 8,395 | 2,166 |

| 2010 | 10,129 | 5,840 | 5,390 | 10,899 | 2,159 |

| Annualized change | 0.8% | 2.7% | 5.3% | 0.9% | 0.0% |

| Life Expectancy at Birth | |||||

| 1980 | 58.6 | 56.6 | 60.2 | 64.4 | 48.2 |

| 2010 | 71.4 | 70.5 | 69.3 | 74.0 | 53.0 |

| Annualized change | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

| Infant Mortality Rate | |||||

| 1960-1964 | 154 | 171 | 131 | 99 | 151 |

| 1980-1984 | 79 | 97 | 69 | 55 | 115 |

| 2005-2009 | 30 | 35 | 38 | 21 | 86 |

| Annualized change (1960-1980) | -3.3% | -2.8% | -3.2% | -2.9% | -1.4% |

| Annualized change (1980-2005) | -3.8% | -4.0% | -2.4% | -3.8% | -1.1% |

| Annualized change (1960-2005) | -3.6% | -3.5% | -2.7% | -3.4% | -1.2% |

| Expected Schooling (Life table estimate) | |||||

| 1980 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 10.1 | 5.7 |

| 2010 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 13.5 | 8.4 |

| Annualized change | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 1.3% |

Life expectancy at birth also contributes one-third of the HDI. Arab States saw substantially greater gains than other regions, rising from 58.6 to 71.4, an almost 13 year gain. In annualized terms, Arab States gained 0.7% per year, compared to 0.5% for Asia and Latin America and just 0.3% for Africa. The UN Population Division's infant mortality rate (IMR) series, which dates back to 1960, shows that IMR was slightly higher in Arab states (154 deaths per 1,000 births) than in Africa (151/1,000) for 1960, whereas today these regions have IMRs of 30 and 86, respectively. Over the 45-year period, Arab States have maintained the highest annualized rate of IMR reduction (3.6%), three times faster than in Africa (1.2%) and one-third faster than in Asia (2.7%). The pace of improvement is slightly faster than that seen in Latin America (3.4%).

Though Arab States did not outperform other regions in schooling, the region kept up with the rapid global pace of improvement. The ―expected schooling‖ of children is a synthetic cohort estimate of the years of schooling a child would expect to complete if current grade-to-grade transition rates applied throughout her life course. It is thus more sensitive to recent policy than the actual schooling measure, which also includes older adults. (3) Expected schooling for Arab states has risen from 8.0 years in 1980 to 11.4 years in 2010, a 1.2% annual gain. By comparison, Asia has gained 1.3% per year and Latin America 1.0% per year.

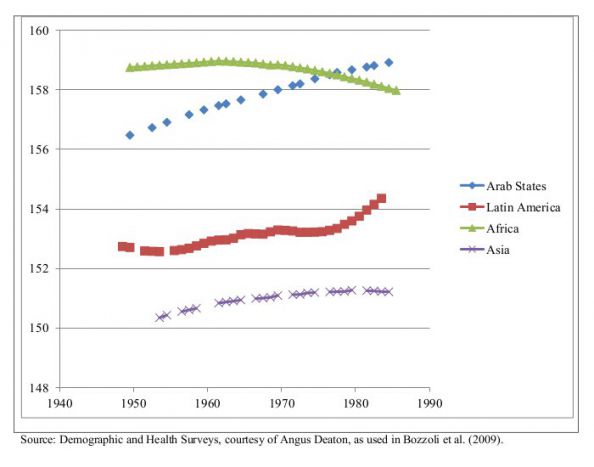

Improvements in early life are further reflected in later adult health status and longevity. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) allow us to track cohort change in the height of women age 15–49. Bozzoli et al. (2009) found a strong association between the probability of dying before age 15 and the height of women age 20–49 in 124 Demographic and Health Surveys from 60 countries. (4) Using these data, Figure 1 tracks cohort change in women's completed height for available DHS samples by region. (5) In the Arab States, women born in 1985 were on average 3cm taller than women born in 1950. Sub-Saharan Africa, by contrast, saw a height decrease, though this may be difficult to interpret in light of selective mortality from the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the inclusion of ever-poorer African states. It is nonetheless illustrative to note the height crossover for women in the two regions, with women in the selected Arab States now taller than those from Sub-Saharan Africa. Adult survival also improved dramatically. World Health Statistics life tables indicate that the female probability of dying between age 15 and 60 for Egypt declined from 18.2% in 1990 to 13.0% in 2009, or a 29% relative reduction.

This human development progress has gone largely underreported, particularly in comparison to the attention paid to persistent deficits in areas such as employment, women's status, human rights, and political autonomy that are often mentioned as causes of the revolutions. Throughout the 2000s, the UNDP Regional Bureau for Arab States produced a series of controversial and widely publicized Arab Human Development reports (HDRs). The most widely publicized was the 2005 report, Towards the Rise of Women in the Arab World, which offered a withering assessment of the physical, social, economic, and political costs, for women and society, of women's underemployment and bias against women and girls (UNDP 2006). The report documented progress in basic health, education, and nutrition, but these findings rarely merited attention in political discourse or popular coverage, where focus lay squarely on the wasted opportunity posed by exclusion of half the population from the public sphere. Other Arab HDRs focused on adolescent opportunity, political freedom, and access to information technology. The tone of rising expectation and indeed the very existence of an Arab HDR illustrate how the development elite had rapidly upgraded their expectations to promote an increasingly ambitious and complex development agenda. Below I argue that an analogous process of mobilization and expectation was also underway at the population level, especially for younger cohorts. The formulation of grievances and expectations begins with an emerging political consciousness.

Human capital and individual political mobilization

The simple proposition that improvements in basic human development increase the capacity for political action is perhaps widely accepted, but the nature and strength of this relationship have rarely been theorized or measured. A human development approach to political agency would account for both enabling and motivating effects. The enabling effect would include a cognitive pathway through which brain development and schooling yield separate but intertwined contributions to political knowledge and analytic ability (Welzel and Inglehart 2005; Campante and Chor 2010). Physical strength and stamina might further enable political action, especially direct action involving protests, nonviolent or violent resistance, and endurance of abuse.

The motivating effects may stem both from participating in human development programs and from those programs‘ outcomes. Schools are one of the most important venues for socialization into formal and informal political institutions, providing civics training, voter awareness and education, and indoctrination (Hannum and Buchmann 2005; Glewwe 2002). Health and nutrition programs also engage populations with government on a variety of levels. Improvements in human capital may also motivate political engagement to the extent that they lead to increased productivity, wealth, or longevity. Just as longevity may increase financial investment and saving, so it might also encourage political participation. At the very least, longevity implies a longer time in which to enjoy the benefits or endure the harms of political change.(6) As socialization is reinforced throughout the life course, the pathways from schooling and longevity to economic wealth may create higher levels of ownership in society, and thus greater vested interest in political outcomes.(7)

Few empirical studies have tested such an elaborate model, and almost no research has been conducted in LDCs. Evidence from advanced democratic societies finds a strong relationship between schooling and political participation (Torney-Putra et al. 2001; Brown and Lichter 2005). A small number of studies have produced similar results for LDCs (Inkeles 1969; Inglehart and Norris 2003). But a bivariate approach does not address whether schooling effects result from learning or socialization (Kam and Palmer 2008; Hannum and Buchmann 2005). Only a very small number of studies have measured the specific relationship between cognitive performance and political action (cite). None of these studies has used an experimental design to separate schooling from the confounding effects of social status and familial self-selection. And no studies have addressed the role of physical functioning in driving political participation.

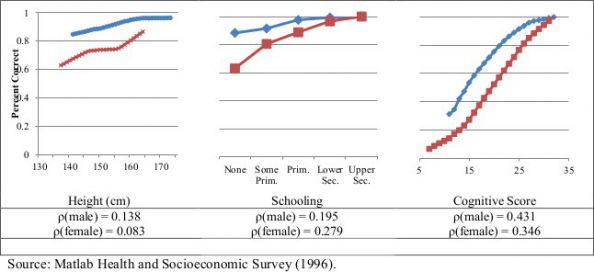

As no dataset collected in the Arab world links anthropometric, psychometric, and political variables—indeed few such datasets exist anywhere in the developing world—I illustrate basic relationships using data from the Matlab Health and Socioeconomic Survey in Bangladesh (Rahman et al. 1996). Bangladesh, like many Arab states, has seen substantial cohort-level change in stature, schooling, and cognition. MHSS data thus offer a rare opportunity to ask whether variations in human capital relate to variations in political mobilization. Respondents were asked whether they could name the prime minister, and the interviewer coded whether they actually gave the correct name. For respondents age 20 to 49, (8) Figure 2 separately plots the unadjusted, bivariate relationships between naming the prime minister and completed height, highest level of schooling, and the results of the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) employed by Barham (2011). (9) Each bivariate relationship is positive and significant, and remains equally so in the presence of wealth controls, which indeed are fully explained by these factors. Unsurprisingly, cognitive performance has a far stronger correlation and captures a much greater range of variation. Cognitive data would clearly be the preferred method for measuring political capability. Nevertheless, both schooling and height would capture significant and unique variation in political awareness in the absence of cognitive data. Even in the presence of cognitive controls (models not shown), schooling remains a significant predictor of political knowledge, suggesting a strong socialization effect, particularly for women.

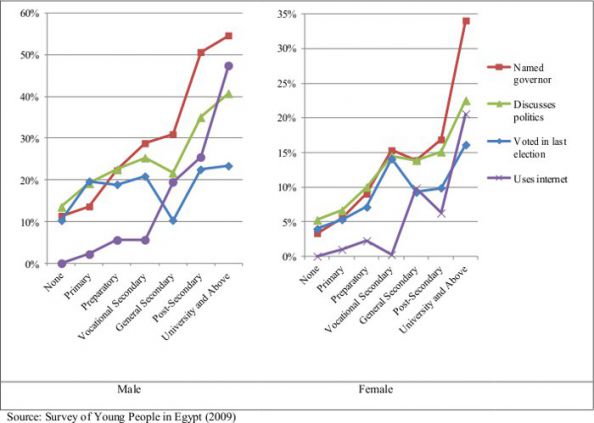

Existing data from the Survey of Young People in Egypt (SYPE) permit a preliminary exploration of the relationship between variation in schooling and a range of political outcomes. The relationship between schooling and whether the individual voted in the previous election was very weak. This result is unsurprising given the limited civic benefits of participating in an uncontested election. The weak individual relationship conceals an even weaker ecological association. Urban governorates like Cairo and Alexandria had substantially higher levels of aggregate schooling than other regions, yet had the lowest share voting, suggesting higher levels of disillusionment in urban areas or higher levels of vote-buying in rural ones.

The relationship between schooling and political mobilization becomes clearer when one looks instead at political awareness or discussion. The self-reported ability to name the governor rose consistently with level of schooling. Males with post-secondary education were 5 times more likely to know the name of the governor than men with no schooling. For females, who had less knowledge of their governors overall, the same ratio was 10 to 1. There was a somewhat weaker but still sizable relationship between level of schooling and whether the individual discussed politics with friends and family. Males were 3 times more likely and females 4 times more likely to discuss politics if they had post-secondary schooling than if they had no schooling at all. This simple bivariate relationship does not indicate whether the schooling effect results from learning, cognition, or socialization, nor does it address any hidden association with physical performance.

Whereas much attention has been paid to the role of the internet and social media in facilitating the revolution, less attention has been paid to the role of human development in internet access. Figure 4, again using SYPE data, presents the average hours per week spent on the internet broken down by sex and highest level of schooling. Respondents with university schooling, who constituted 15% of the male and 14% of the female respondents, were far more likely than other groups to use the internet. Even among males with only secondary schooling, 20% reported using the internet sometimes. Improvements in human development can thus be associated with the increased political activity and use of social media that were so critical to revolutionary events. But these effects on political participation would have had little political impact in the absence of changes in expectations and attitudes.

Human capital and life course expectations

The relationship between past human development progress and current popular expectations is essential to understanding the context of political change. Popular and academic experts have widely interpreted the Arab Spring as resulting from the failure of governments to meet current needs, specifically for employment and food security. But these particular crises did not occur in a vacuum. While the Arab States experienced the same global economic recession as other nations, the specific welfare ramifications and policy contexts of these crises were conditioned by decades of progress in basic human development. Improvements in early-life human development are often followed by increasing physical and social needs and expectations that are more difficult for governments to address. As noted above, rising expectations may result from social aspiration or the inertia of the development agenda, but they also derive from specific physiological and social implications of the life course model.

For governments, addressing this shift in popular expectation is not merely a matter of engaging in more expensive, enduring or complicated policy agendas that are nonetheless state-centric. Rather governments are increasingly expected to engage in more subtle legal, institutional and regulatory decisions aimed at enabling individual or market-based solutions. The chronic failure of a government to grapple with such challenges poses a twin threat to regimes whose survival depends on patronage and service provision. First, as individuals increasingly meet new challenges on their own or through markets, they may be freed from dependency on the government. At the same time, the government may draw increasing blame for being unable to follow past successes in human development with achievements in growth, human rights and institutional change. I offer two examples of this process, each of which relates to the specific social-physiological implications of life course theory.

Food security crisis or nutritional transition?

The first pattern relates to rising caloric demands. One common perception holds that the Arab Spring was a response to a global food security crisis, possibly related to global warming (Johnstone and Mazo 2011). There was surely a rise in the price of food and in the share of household budgets expended on food since 2008, with substantial implications for welfare (Jones et al. 2009). But the particular food crisis faced by Arab states also reflected rapid development shifts in level and composition of food consumption and a diminished ability of the state to manage these relationships.

Figure 4 charts the growth in caloric consumption per capita per day from 1961 to 2002 for four major developing regions and Egypt. The Arab States had by far the fastest growth in caloric consumption of any region. In 1961, average consumption (1,966 per day) was actually slightly lower than in Sub-Saharan Africa (2,134) and much lower than in Latin America (2,292). But average consumption surpassed that of Sub-Saharan Africa in 1966 and that of Latin America in 1980. While some of this effect relates to the rising price of oil, Egypt, with relatively limited oil resources, has seen even more rapid increases in caloric consumption. Similar gains were seen in Syria, among other states.(10) While shifts were driven in large part by food prices and rising social and consumption aspirations (Popkin and Gordon-Larsen 2004), they are also the direct consequence of physiological consequences of human development. One corollary to Barker's thrifty phenotype hypothesis holds that taller populations with faster metabolisms will in fact need more food. Larger bodies can be more productive, but only if they receive additional nutrients that might not have been available in earlier generations.

In spite of aggregate improvement, the shift in caloric demand can lead to increased household uncertainty in food supply, creating new policy imperatives. Many governments support prices or distribute strategic stocks to meet basic caloric needs at the subsistence level, but as diets become higher in calories and protein, it becomes more difficult to manage their production, distribution, and price. These difficulties stem from the total volume of consumption, the diversity of food sources, the increasing complexity of food supply chains for products like meat, and the increasing availability of imported food. They were further exacerbated by neoliberal institutional pressures to reduce state expenditure. Since 1990 Egypt's once-lavish food subsidy network has dropped by half as a share of government expenditure, now covering only the poor and focusing primarily on bread (Trego 2011).

The removal of subsidies itself would not be a problem if household income growth and domestic food production could improve food availability and security. Over the same time period, many transitional countries in Latin America adopted conditional cash transfer programs and other methods of reducing inequality in consumption, if not income itself (cite). Yet in the Middle East, accelerating GDP growth was accompanied by considerable household-level uncertainty, with a large share of households moving above and below the poverty line, even as aggregate levels of welfare rose (Marotta 2011). As food prices rose post-2008, the welfare consequences of household economic fragility became more readily apparent, and the problem was far too advanced for effective state intervention.

While the overall failure to adopt a new generation of poverty and food policies may have provoked widespread popular anger at the government, the reduction of food subsidies may also have represented a form of popular liberation from government patronage. A government with the capacity to smooth over food shortages has considerable leverage over the population. Many Arab nations have well-established systems of bread rationing. In the past, rations served as both a lifeline for the populace and a tool of manipulation for many governments, a tool that could be far more effective at curbing dissent than direct pressure (Salevurakis and Abdel-Haleim 2008). By the time of the Arab Spring, rising caloric needs and alternate sources of supply reduced the leverage of government in using entitlement cuts as a source of counterrevolutionary pressure. This was most obvious in Egypt. After the Mubarak government declared a state of emergency and sent the military to the streets on January 29, the supposed loss of state control was used as a rationale for closure of shops providing subsidized baladi bread, an effort that only served to degrade regime credibility further. In Egypt and in many Arab States, past dietary change set the stage for revolution, increasing the physical capabilities of the population, highlighting government failures to reduce poverty even further, and removing the food subsidy system as a pillar of regime survival.

Unemployment crisis or adolescent transition?

The social and physiological implications of past human development for current regime strength are even more apparent in the emergence of extended adolescence. Research on societies from premodern to postindustrial has illustrated the association between human development and the emergence of adolescence as a unique life stage (Kaplan 1997, Kaplan et al. 2003). This shift is intimately related to increasing longevity and mortality risk. As life spans increase and the risk of premature death in prime-age adulthood decreases, the cumulative life course returns to increased human capital investment increase dramatically, thereby opening up the need for an extended adolescence characterized by the diversification of activities away from subsistence production and towards schooling. This longevity effect is further amplified by enhanced physical and cognitive capabilities, which allow individuals to engage in higher education. Families and societies may have further incentive to encourage this shift as a pathway to increasing growth and opportunity (Becker 1991).

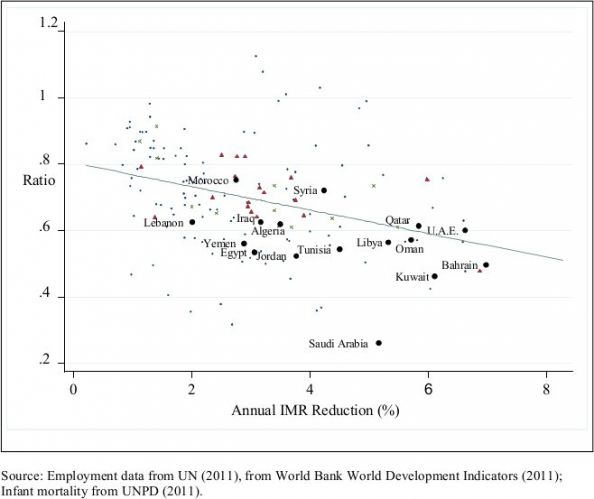

It is in this light that we may be able to reinterpret the most commonly cited explanation for the Arab Spring, which relates to the low rate of youth employment (Assad 2011). While youth employment rates were low in many Arab states, they should have been declining as a result of past human development. Figure 5 depicts the strong relationship between past declines in infant mortality (from 1960 to 1985) and low youth employment in developing countries. Using indicator data from the International Labor Organization (ILO), I divide the employment rate among 18 to 29 year-olds by the employment rate for all ages combined. (11) The correlation between the youth employment ratio and past infant mortality decline is -0.54, stronger than the bivariate correlation of past fertility or current schooling to youth employment (not shown). Whereas nations trapped in a daily struggle for basic physical sustenance may have very high levels of youth employment, youth throughout the Arab world, as in other societies undergoing life course transition, were naturally shifting toward higher levels of life cycle investment and accumulation, with a concomitant decline in youth employment.

While the adolescent transition is thus a marker of past success and a precursor of further human capital accumulation, it nonetheless creates new pressures on society and government. In the past decade two high profile publications have addressed the challenges of meeting the needs of today's large youth cohorts, the product of declining fertility and improved survival. The US National Research Council's Growing up Global and the 2007 World Development Report highlighted the advantages and challenges facing what will likely come to be the largest cohorts in human history (Lloyd 2005; World Bank 2006). Compared to earlier cohorts they were endowed with better health and schooling; connected to global social and economic networks; and protected by national programs and global charters aimed at ensuring a safe adolescence. At the same time, each report highlighted the pressures and challenges of navigating key transitions into work, citizenship, marriage and parenthood; the difficulty of making policy to achieve these goals; and the threat of disorder if expectations were not achieved. Creating sufficient employment to justify delayed adolescence was but one of many challenges facing governments.

We can thus consider the challenges facing many Arab States in light of the benefits and burdens of extended adolescence. Some Arab States had even lower levels of youth employment than would be predicted simply from infant mortality reduction alone. Whereas the regression line in Figure 5 suggests that Egypt, Tunisia, and Jordan might have expected a youth employment ratio of 0.7, in fact it was more like 0.55, lower than in Singapore or Cyprus, though not as low as in South Korea or Chile. The combination of high adolescent expectation and low workforce mobilization created both a motive for popular dissatisfaction and an educated, mobilized population to engage in unrest. In Syria and Morocco, levels of youth employment, while lower than in the past, were perhaps higher than expected given their stages of capability development.

Rather than focusing on underemployment per se, we might begin to examine young people's broader expectations for future employment and advancement given the progress they have witnessed during their lifetimes. Campante and Chor (2010) find that the association between schooling and political participation is lower in countries with higher returns to human capital. While the authors interpret this to mean that the opportunity costs of political engagement are higher when growth is high, a complementary interpretation would be that young people in societies with low returns to human capital have both the time and a reason to engage in politics.

We may also move beyond economic activities to consider other critical life transitions like family formation. Rising age at marriage is also frequently associated with increased longevity and extended adolescence. The increase in age at marriage, particularly for women, has been rapid in most Arab States, particularly less wealthy ones (Rashad and Osman 2001). In Maghreb nations such as Libya and Morocco, mean age at first marriage for women is now close to 30 (Tabutin and Schoumaker 2005). This does not necessarily imply that the Arab Spring was a marriage crisis, but neither do employment numbers necessarily imply that it was an economic crisis. Instead, human development sets in motion multiple social conditions in which higher expectations, greater uncertainty, and policy complexity can lead to unrest. Extended adolescence creates the expectation of better jobs and marriages even as it delays the arrival of any job or any marriage. This can lead to tension in any society, particularly among a highly capable young generation, but may be particularly profound when the state seems unable to manage the strain.

Changing expectations, changing attitudes

Given the new development challenges facing Arab societies, can we observe the emergence of changing political attitudes and values in the run-up to the Arab Spring? Elite forums like the Arab Human Development Report conveyed a high level of dissatisfaction and an urgency for change, but did such sentiment also exist at the population level? Such gradual value shifts would not be observable in electoral activity or stated preferences, particularly given curbs on electoral competition and freedom of expression in place at the time. Instead we must look to latent constructs. Inglehart's post-materialism index offers one measure of the shift "from giving top priority to physical sustenance and safety, toward heavier emphasis on belonging, self-expression and the quality of life" (Inglehart 1981). The post-materialism index asks respondents to rank the importance of a range of abstract values like unity, autonomy, and expression against material concerns like economic growth, personal security, and national security. (12)

Post-materialism carries both direct and latent implications for political change. As a direct measure, it indicates whether individuals are more concerned with complex, higher-order needs or basic ones. As a latent factor, Inglehart argues, post-materialism captures a detachment from the existing order and openness to dramatic change:

- despite their favored socioeconomic status, Post-Materialists would be relatively supportive of social change, and would have a relatively high potential for unconventional and disruptive political action.... Post-Materialists have a larger amount of psychic energy available for politics, they are less supportive of the established social order, and, subjectively, they have less to lose from unconventional political action than Materialists. (Inglehart 1981, 890)

This psychic energy was first operationalized in terms of relative socioeconomic position or security, for instance in tracking cohort value change in post–Marshall Plan Germany and Japan. More recent work has tied the post-materialist shift to cognitive change and subjective aspiration. Welzel and Inglehart (2005) suggest that enhanced physical and cognitive resources increase the objective basis for exercising freedom and self-expression. They posit a process of aspiration adjustment whereby "human beings tend to adjust their subjective aspirations to their objective means" (emphasis in original). However, they operationalize the cognitive dimension only in terms of schooling and the physical dimension only through national agricultural production.

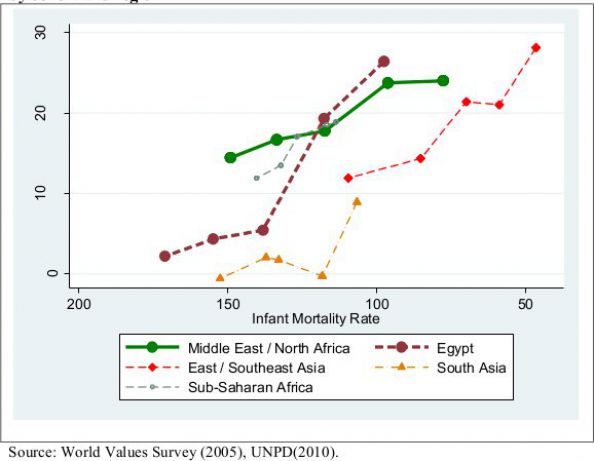

To address the physical determinants of value change over the life course, Figure 6 depicts variation in the relationship between infant mortality at the time of birth and post-materialism in later life for birth cohorts from 1960 to 1980 in the Arab States, Egypt, East Asia, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Post-materialism data come from the fourth World Values Survey, occurring between 1999 and 2004 (WVS 2005). (13) Among our Arab States, in addition to Egypt, WVS included Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia. None of these other nations has yet experienced regime change, though all have seen some protest and all except Algeria have seen substantial political reform. These data also exclude the 1985 and 1990 birth cohorts, which saw substantial IMR reduction in Arab states and were pivotal in the Arab Spring. Following Inglehart (1997), the y-axis measures a net post-materialism index calculated as the prevalence of post-materialism minus the prevalence of materialism. (14) The x-axis indicates the country-level IMR at the time of birth using a reverse scale. The slope of the lines indicates the strength of the relationship between infant mortality and post-materialism.

All regions experienced declining IMR and rising post-materialism. At the country-cohort level, the bivariate correlation between IMR and post-materialism was 0.45. A bivariate regression coefficient of 0.14 implies a one-percentage-point rise in net post-materialism for every IMR reduction of 7 deaths per 1,000 births. Arab states saw a 13-percentage-point rise in net post-materialism between the 1960 and the 1980 birth cohorts (from 12% to 25%), a substantially greater gain than is observed for South Asia (9 percentage points) or Sub-Saharan Africa (5 percentage points). Only East Asian nations saw a more pronounced value shift (20 percentage points). Developed countries as a whole experienced a 10-percentage-point gain over the period. The strength of post-materialism gain in the Arab States and East Asia as a whole is entirely explained by their greater extent of IMR reduction compared to the other regions, not by the slope of the IMR / post-materialism relationship, which was comparable across regions.

The regional pattern for Arab States conceals a more dramatic value shift in Egypt. The extraordinary rise in post-materialism experienced by Egypt was driven not by mortality alone, but also by a steeper slope in the relationship between IMR and post-materialism. Here we may begin to observe a synergism between physiological and social change. Inglehart (1981) argued that value change would derive not from declining individual scarcity alone, but from a socialization process in which members of a cohort grow accustomed to a widespread sense of physical security among their entire cohort. In spite of continued limitations on political rights and the life course challenges noted in the previous section, this argument well describes Egyptian cohorts born in the 1980s and 1990s. The benefits of early life health, nutrition, and schooling penetrated every corner of the nation, with some of the most rapid gains coming in remote areas of the upper Nile. The collective sense of security was also reflected in the rise of higher education, in middle-class imagery in bourgeois popular culture, and in the use of social media. While physical security drove higher aspirations, both material and non-material, it may also have served as a platform for widespread mobilization against a regime that could not help citizens to meet their aspirations.

Conclusion

There is perhaps no better example of the role of human development in political change than the Arab Spring. While many specific events triggered a sudden wave of uprising, the indicators of imminent change were present in multiple dimensions of human development across many societies. No developing region had seen such improvements in multiple indicators of human capability, reflected for example in declining child mortality, increased schooling, and increased stature of women. In the Arab States, unlike Asia, these changes emerged through government development interventions, not in tandem with rapid GDP growth. Improvements in human capital promoted both the capability and the opportunity to engage in political discourse and connect to interactive media. More importantly, human development set in motion a set of rising expectations, both physiologically and socially determined, that placed considerable pressure on government, particularly in the context of extended adolescence. The urgent demand for reform was apparent in elite forums like the Arab Human Development Report and in measures of cohort change in values and attitudes. While human development did not make the Arab Spring inevitable, it surely increased the probability of uprising well beyond any widely perceived risk.

Perhaps the most widely accepted view of the Arab Spring is that it resulted simply from extraordinarily large youth cohorts (Cincotta et al. 2003). Loosely combining Malthusian principles with social-psychological models of adolescent problem behavior, the "youth bulge hypothesis" emphasizes the potential for large youth cohorts, particularly males, to engage in violent social and political upheaval, resulting in chronic disorder and violence. Indeed, leading proponents of the youth bulge theory forecast that the Arab world would see democratic transition only after these large cohorts passed into middle age (Cincotta 2009).

Instead, young cohorts in the Arab world, restive yet physically healthier and more skilled than any before them, played a pivotal role in bringing about popular transitions. Most were peaceful. The transition in Libya, while needlessly violent, has nonetheless resulted in a fairly rapid transfer of power. Government violence in Syria has belied the widespread use of non-violent resistance.

The Arab Spring thus illustrates the limitations of simplistic demographic determinism. By focusing on mere numbers of adolescents, the youth bulge hypothesis ignores how the human capital of youth cohorts might dictate the nature and ultimate success of the unrest. By focusing narrowly on current youth frustrations over unemployment, it ignores young people's long-term aspirations for healthy lives, jobs, marriages and society. This combination of capability, aspiration and frustration may undergird a rational decision to rebel. Finally, it is important to remember that it takes a whole society, not one cohort, to engage in successful rebellion, and that the development transition affected every cohort in some way. A human development approach to revolution would instead consider the size, capability and solidarity of multiple cohorts operating in conflict and concert. Such a model should also speak to models of political agency and elite incorporation currently employed in political science.

A human development approach has important implications for development policy and political risk. First, self-serving autocrats may reassess the value of human development interventions that may sow the seeds of their own demise. Consider Libya, which for years drew comparisons to North Korea or Myanmar for its repressive political and rights regimes and erratic leadership. Yet Libya sustained rapid and broad-based improvements in health and schooling even as Myanmar stagnated and North Korea dipped into mass starvation. Whereas Libya's scattered resistance movements quickly transformed into a highly organized self-governing entity, Myanmar's lone resistance movement was thoroughly isolated and crushed while North Korea has seen no resistance for years.

Second, the emergence of indigenous, popular rebellions in the Arab States offers partial vindication to the laissez faire approach of foreign donors who focused on basic needs at the expense of democracy promotion. In supporting autocratic regimes in the short-run, donors may have ultimately hastened their demise. Long-term political outcomes do not fully vindicate such an approach, but they do illustrate an important impact of development programs that is widely assumed yet seriously undertheorized and unmeasured. Future research must address specific causal impacts of human development on political engagement, social expectations, and popular dissent. Tests of these hypotheses depend on panel data sets like MHSS that link programmatic variation in anthropometric and psychometric well-being to a wide range of political and attitudinal variables.

For while Libya and Egypt's popular revolution may be preferable to North Korea's stagnant misery, they may still be considered sub-optimal compared to a peaceful transition. Even the most successful revolutions of the Arab Spring included short-term violence, economic crisis, and violence against minorities. We can thus consider the value of new basic health and development interventions that also work to address the social determinants of health and establish community engagement, oversight, and leadership over programs. If these could foster gradual shifts to democracy with greater tolerance for minority and women's rights, then they should be encouraged. Designing programs that achieve epidemiological and political goals with simultaneous efficacy will require extensive modeling, program design, and evaluation.

The final chapters of the Arab Spring are yet to be written. We do not yet know whether this will be a pivotal moment of liberation, a gateway to recurring instability, or simply a damp squib. But the preceding analyses and framework suggest that the causes of the movement were not merely reflexive, but reflective of ongoing shifts in the basic parameters of human development. On multiple indicators of human development, Arab States today bear far greater similarity to the nations of Eastern Europe in the late 1980s than is widely recognized, and far less similarity to Iran in the late 1970s. Table 2 compares life expectancy, infant mortality, and expected schooling for Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, and Yemen to earlier revolutionary contexts. Though Yemen does not compare favorably to the ex-Eastern Bloc countries in 1989, Tunisia and Libya today are comparable to Hungary in 1989; Egypt would be more comparable to Romania in 1989. If human development does shape the pathway to revolution, we may hope that it will also determine the endurance and ultimate success of a revolution.

(1) Separately, work by Eileen Crimmins and others demonstrates an immunological pathway whereby repeated episodes of inflammation due to infectious disease can promote negative inflammatory responses such as the buildup of plaques in the arteries, leading to atherosclerosis (Crimmins and Finch, 2004).

(2) The stunting paradigm also serves as a partial resolution to the century-old debate on the relative importance of nutritional changes versus health interventions (McKeown 1976). As the end result of chronic insufficiency of nutrients, stunting results from both a lack of nutritional intake and reduced nutritional absorption due to a range of childhood infectious diseases (Deaton 2005).

(3) It is also somewhat more susceptible to tempo effects than actual schooling measures. Libya ranks higher on expected schooling than the United States (16.5 versus 15.7 years) even though the US ranks much higher on tertiary enrollment (72% vs. 48%), according to UNESCO (2009).

(4) There is significant regional variation in completed height at baseline that has been attributed to both genetics and self-selection, but changes in height over time are strongly associated with changes in nutrition and disease (Deaton 2005; Bozzoli et al. 2008).

(5) A few caveats are worth noting. As DHS is funded by the US Agency for International Development, case countries tend to be US allies. The set of Arab states includes only Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Yemen. Conveniently, each is undergoing a political transition of one form or another. As DHS is primarily a survey of basic health needs, countries with the most dramatic health improvements will be excluded from DHS or "graduate" out of the DHS pool, while countries with stagnant gains might find their way into the pool. However, most of the cohort variation in this example occurs within survey round, not across rounds.

(6) Preston (1985) highlighted how longevity leads to increased political engagement by creating a second period of public dependency in old age. Incentives for political participation may rise not just among the aged, but among younger individuals seeking to ensure the support of their parents and future selves.

(7) A few studies, however, note that high wages may encourage a shift in time use from political activity to wage-earning activity, though this would be more likely in societies with high income returns to human capital (Campante and Chor 2010).

(8) Similar relationships hold when those over age 50 are included or when one focuses within younger cohorts that benefited from extensive child health programs and tend to be taller on average.

(9) A simplified mini-mental state examination (MMSE) was adapted to have cultural relevance to Bangladesh and Bengali language and to be valid in a population with high levels of illiteracy (Barham 2011). It included 33 questions relating to the domains of orientation, attention-concentration, registration, recall, language, and calculation.

(10) While the distribution of calories in Arab states was not necessarily equitable, UNICEF reports that the percentage of under-fives suffering from underweight in 2003–2009 was 14% in the Middle East, compared to 47% for south Asia and 27% for sub-Saharan Africa. It is also worth noting that the caloric rise is not unambiguously positive, as some consumption levels, particularly in Egypt, exceed a healthy level.

(11) Typical unemployment rates exclude individuals who are out of the labor market from the denominator, but this employment measure simply asks who is working and who is not, whether those not working are in school, looking for work, or frustrated.

(12) Materialist values include maintain order in the nation, fight rising prices, maintain a high rate of economic growth, make sure that this country has strong defense forces, maintain a stable economy, and fight against crime. Post-material values include move toward a society where ideas count more than money, give people more say in decisions of government, protect freedom of speech, give people more say in how things are decided at work and in their community, try to make our cities and countryside more beautiful, and move toward a friendlier, less impersonal society.

(13) For Latin America, the countries were Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela; for east Asia they were China, Indonesia, Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam. For south Asia they were Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. For sub-Saharan Africa they were Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda.

(14) Inglehart and Abramson (1994) explain, "Respondents are classified as 'high‘ on the 12-item materialist/postmaterialist values index if they gave high priority to at least three of the five postmaterialist goals (i.e., as one of the two most important goals out of each group of four goals); they are classified as 'low‘ if they chose none of the five postmaterialist goals among their high priorities."

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Simon Johnson. 2007. “Disease and Development: The Effect of Life Expectancy on Economic Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 115(6): 925-985.

- Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2001. ―A theory of political transitions,‖ American Economic Review 91(4): 938–963.

- Al-Awadi, Hesham. 2004. In Pursuit of Legitimacy: The Muslim Brothers and Mubarak, 1982–2000. New York: Tauris.

- Arora, Suchit. 2001. ―Health, human productivity, and long-term economic growth," Journal of Economic History 61(3): 699–749.

- Barham, Tania. 2011. "Enhancing cognitive functioning: Medium-term effects of a health and family planning program in Matlab," Applied Economics, forthcoming.

- Barker, David J. P. 1998. Mothers, Babies and Disease in Later Life. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Barker, David J. P. and Clive Osmond. 1986. ―Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales," Lancet 27(8489): 1077-81.

- Becker, Gary S. 1991. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Boswell, Terry and William J. Dixon. 1993. "Marx's theory of rebellion: A cross-national analysis of class exploitation, economic development, and violent revolt," American Sociological Review 58(5): 681–702.

- Bozzoli, Carlos, Angus Deaton, and Climent Quintana-Domeque. 2009. ―Adult height and childhood disease," Demography 46(4): 647–669.

- Brown, Brian J. and Daniel T. Lichter. 2005. ―Childhood disadvantage, adolescent development, and pro-social behavior in early adulthood,‖ in Timothy Owen (ed.), Advances in Life Course Research, vol. 11. Greenwich, CT: Elsevier/JAI Press.

- Caldwell, John C. 1986. ―Routes to low mortality in poor countries,‖ Population and Development Review 12(2): 171–220.

- Castelló-Climent, Amparo. 2008. "On the distribution of education and democracy," Journal of Development Economics 87: 179–190.

- Cincotta, Richard P. 2009. "Half a chance: Youth bulges and transitions to liberal democracy," ECSP Report Issue 13, Environmental Change and Security Program, Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars.

- Cincotta, Richard P., Robert Engelman, and Daniele Anastasion. 2003. The Security Demographic: Population and Civil Conflict after the Cold War. Washington, DC: Population Action International.

- Crimmins, Eileen M. and Caleb E. Finch. 2006. ―Infection, inflammation, height, and longevity,‖ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(2): 498–503.

- Cutler, David, Angus Deaton, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. 2006. ―The determinants of mortality,‖ Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(3): 97–120.

- Deaton, Angus. 2005. ―Height, health, and development," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(33): 13232–13237.

- FAO. 2009. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2009: Addressing Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- FAO. 2011. FAOStat Statistical Database. http://faostat.fao.org/default.aspx

- Fogel, Robert W. 1994. ―Economic growth, population theory, and physiology: The bearing of long-term processes on the making of economic policy," American Economic Review 84(3): 369–395.

- Fogel, Robert W., and Dora L. Costa. 1997. ―A theory of technophysio evolution, with some implications for forecasting population, health care costs, and pension costs," Demography 34(1): 49–66.

- Glewwe, Paul. 2002. "Schools and skills in developing countries: Education policies and socioeconomic outcomes," Journal of Economic Literature 40(2): 436–482.

- Goldstone, Jack, et al. 2010. "A global model for forecasting political instability," American Journal of Political Science 54(1): 190–208.

- Grynkewich, Alexus. 2008. ―Welfare as warfare: How violent non-state groups use social services to attack the state," Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 31(4): 350–370.

- Habermas, Jurgen. 1970. "Toward a theory of communicative competence," Inquiry 13: 360–375.

Haggard, Stephen and Robert R. Kaufman. 1997. "The political economy of democratic transitions," Comparative Politics 29: 263–283. - Hannum, Emily and Claudia Buchmann. 2005. "Global educational expansion and socio-economic development: An assessment of findings from the social sciences," World Development 33(3): 333–354.

- Hughes, Barry B. Randall Kuhn, Cecilia Mosca Peterson, Dale S. Rothman, and José Roberto Solórzano. 2010. Improving Global Health: Forecasting the Next 50 years. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald. "Post-materialism in an environment of insecurity," American Political Science Review 75: 880–900.

- ———. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald and Pippa Norris. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Inkeles, Alex. 1969. "Participant citizenship in six developing countries," American Political Science Review 63(4): 1120–1141.

- Johnstone, Sarah and Jeffrey Mazo. 2011. "Global warming and the Arab Spring," Survival 53(2): 11–17.

Jones, Nicola, Caroline Harper, Sara Pantuliano, and Sara Pavanello. 2009. "Impact of the economic crisis and food and fuel price volatility on children and women in the MENA region," Overseas Development Institute Working Paper 310, London: ODI. - Kam, Cindy D. and Carl L. Palmer. 2008. "Reconsidering the effects of education on political participation," Journal of Politics 70(3): 612–631.

- Kaplan, Hillard. 1997. "The evolution of the human life course," in Kenneth Wachter and Caleb E. Finch (eds.), Between Zeus and Salmon: The Biodemography of Aging. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, pp. 175–211

- Kaplan, Hillard, Jane Lancaster, and Arthur Robson. 2003. "Embodied capital and the evolutionary economics of the human life span," Population and Development Review 29 (Supplement: Life Span: Evolutionary, Ecological, and Demographic Perspectives): 152–182.

- Lerner, Daniel. 1958. The Passing of Traditional Society: Modernizing the Middle East. New York: Free Press.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1959. "Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy," American Political Science Review 53: 69–105.

- Lloyd, Cynthia B. (ed). 2005. Growing up Global: The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press, 2005.

- McKeown, Thomas. 1976. The Modern Rise of Population. New York: Academic Press.

- McNicoll, Geoffrey. 2006. "Policy lessons of the East Asian demographic transition," Population and Development Review 32(1): 1–25.

- Marotta, Daniela, Ruslan Yemtsov, Heba El-laithy, Hala Abou-Ali, Sherine Al-Shawarby. 2011. Was Growth in Egypt Between 2005 and 2008 Pro-Poor? From Static to Dynamic Poverty Profile. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5589.

- Moore, Barrington. 1966. The Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon.

- Omran, Abdel R. 1971. "The epidemiological transition. A theory of the epidemiology of population change," Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 49(4): 509–538.

- Popkin, B. M. and P. Gordon-Larsen. 2004. "The nutrition transition: Worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants," International Journal of Obesity 28: S2–S9.

- Preston, Samuel H. 1975. ―The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development,‖ Population Studies 29(2): 231–248.

- Przeworski, Adam and Fernado Limongi. 1997. "Modernization: Theories and facts," World Politics 49: 155–183.

- Rashad, Hoda and Magued Osman. 2001. "Nuptiality in the Arab countries: Changes and implications," in Nicholas S. Hopkins (ed.), The New Arab Family. Cairo: American University Press, pp. 20–50.

- Reich, Michael R. 1995. "The politics of health sector reform in the developing countries: Three cases of pharmaceutical policy," Health Policy 32: 47–77.

- Rudra, Nita. 2005. Globalization and the strengthening of democracy in the developing world. American Journal of Political Science 49(4): 704–730.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. 2001. Macroeconomics and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development: Report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Salevurakis, John William and Sahar Mohamed Abdel-Haleim. 2008. "Bread subsidies in Egypt: Choosing social stability or fiscal responsibility," Review of Radical Political Economics 40 (1): 35–49.

- Schubert, Hermann and Daniel Koch. 2011. "Anthropometric history of the French Revolution in the Province of Orleans." Economics and Human Biology 9: 277-283.

- Sen, Amartya. 1990. "Development as capability expansion," in Keith B. Griffin and John B. Knight (eds.), Human Development and the International Development Strategy for the 1990s. London: Macmillan: 41-58.

- ———. 1993. "Capability and well-being," in Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum (eds.), The Quality of Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ———. 1999a. Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

- Survey of Young People in Egypt (SYPE). 2009. Public Release Data File. The Population Council Regional Office for North Africa and West Asia. www.popcouncil.org/projects/234_SurveyYoungPeopleEgypt.asp

- Tabutin, Dominique and Bruno Schoumaker. 2005. "The demography of the Arab world and the Middle East from the 1950s to the 2000s: A survey of changes and statistical assessment," Population (English selection) 60: 505–616.

- Thornton, Arland. 2001. "The developmental paradigm, reading history sideways, and family change," Demography 38(4): 449–465.

- Torney-Putra, Judith, Rainer Lehmann, Hans Oswald, and Wolfram Schulz. 2001. Citizenship and Education in Twenty-eight Countries: Civic Knowledge and Engagement at Age Fourteen. Amsterdam: IAEEA.

- Trego, Rachel. "The functioning of the Egyptian food-subsidy system during food-price shocks," Development in Practice 21(4–5): 666–678.

- Uauy, Ricardo, Juliana Kain, Veronica Mericq, Juanita Rojas, and Camila Corvalan. 2007. ―Nutrition, child growth, and chronic disease prevention," Annals of Medicine 40(1): 11–20.

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD). 2009. World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision, Population Database. New York: United Nations. http://esa.un.org/unpp/.

- UNPD. 2006. The Arab Human Development Report 2005: Towards the Rise of Women in the Arab World. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2011. International Human Development Indicators. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/data/.

- Victora, Cesar G., Linda Adair, Caroline Fall, Pedro C. Hallal, Reynaldo Martorell, Linda Richter, and

- Harshpal Singh Sachdev. 2008. ―Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital," Lancet 371: 340–357.

- Weil, David N. 2007. ―Accounting for the effect of health on economic growth,‖ Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3): 1265–1306.

- Welzel, Christian and Ronald Inglehart. 2005. "The role of ordinary people in democratization," Journal of Democracy 19(1): 126–140.

- World Bank. 2006. World Development Report 2007: Development and the Next Generation. Washington: The World Bank.

- World Values Survey. 2005. Official Data File v.20090901, 2009. World Values Survey Association (www.worldvaluessurvey.org).

Randall Kuhn is Assistant Professor and Director of the Global Health

Affairs Program

at the Josef Korbel

School of International Studies, University of Denver (2006-present).

His work brings a

wide array of methods and data sources to bear on the connections

between health,

population, and development. He is affiliated with the Masters of

Development Practice,

Certificate in Humanitarian Assistance, Frederick S. Pardee

Center for

International Futures, and DU Kibera Working Group. He is a Research

Associate

of the Institute of

Behavioral Science and the Center for Asian Studies at University

of Colorado-Boulder.

About Us // Privacy Policy // Copyright Information // Legal Disclaimer // Contact

Copyright © 2012-2018 macondo publishing GmbH. All rights reserved.

The CSR Academy is an independent learning platform of the macondo publishing group.