Stakeholder Management – An Introduction

The landscape of business and enterprise policy is subject to almost unparalleled change. An ever-increasing majority of corporate and institutional management boards find themselves operating in a networked world of interests and opportunities for influence. In addition to primary stakeholders such as shareholders, customers, suppliers, and employees, secondary and tertiary stakeholder groups are increasingly making regulatory, social, political, and ethical demands on businesses.

Public and social stakeholder groups are increasingly seeking to bring their influence to bear on corporate decision making and investment. Politicians have discovered social risk-management and are increasing their regulatory requirements on businesses and commercial sectors through their legislative powers; NGOs draw attention to abuses and irregularities by means of effective and high-quality media campaigns. At the same time, the market place of public opinion is going through fundamental and rapid changes: The established media are beginning to lose their capacity to lead; opinions are formed in ways that are more direct, digital, and decentralized; and transparency and dialogue are the order of the day for almost all businesses. Communications with external as well as internal stakeholders rely increasingly on substantive content, and close and resilient relationships with stakeholders are an important factor for success in business.

In the future, the currently still dominant focus on shareholders and target groups will no longer be able to cope with the rapid pace of change in the business environment. Shareholders are an important stakeholder group for sustainable business success, but not the only such group. Nowadays, the task of a future-proof and sustainable strategy is rather that of weighing up the requirements of politics, society, business, and science and aligning them with corporate goals. The so-called license to trade depends not only on dialogue with all relevant interest groups and opinion leaders: Stakeholders and target groups do not simply expect information about activities and decisions from businesses, they want instead to be actively involved and integrated in discussions and decision-making processes.

Businesses and institutions are therefore confronted with a dual task: (1) What are the (new) procedures that we need to establish for the involvement and participation of external and internal stakeholders? (2) What kinds of interactive and communicative innovations might take us beyond information exchange and simple dialogue with stakeholders and create added value?

It is these challenges that are investigated in a new report, for which we interviewed around 100 stakeholder managers from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. The study is titled “Stakeholder Integration: the contribution made by corporate communications and sustainability management to value creation.” It is a project being carried out through a cooperation between Lintemeier Stakeholder Relations, Knobel Corporate Communications, and the MHMK (Macromedia University for Media and Communication) and serves as a descriptive analysis of the current situation. It provides unique insights into the structure of stakeholder management; identifies its substantive and methodological foci; describes its fields of activity and how its operative managers understand their roles; and identifies different models of integration of internal as well as external stakeholders. The companies surveyed were divided into four roughly equal groups according to sales volume: up to €100 million, up to €500 million, up to €5 billion, and over €5 billion. Here we describe the most important findings from the results of the study.

The philosophy of corporate leadership is undergoing a paradigm shift. In the future, a strong orientation toward shareholders among managers will be complemented by a greater emphasis on a stakeholder approach, one which recognizes that the providers of capital represent a group with legitimate, but not exclusive, claims on companies. The rapid pace of change in the business environment and the need for speed and flexibility in strategic decision making mean that early involvement in the strategic process of groups with legitimate interests – recognizing those interests, dealing with them, and managing them – is essential. The interests of (often critical) social groups, in particular, are frequently articulated to businesses and pursued in public – sometimes with great professionalism. This calls for corporate management that works through – and not against – such interests in order to enable sustainably effective corporate decision making.

Over the long term, actions that conflict with perceived social values will jeopardize an organization. Conversely, potential gains can only be realized if stakeholders’ interests are consistently integrated into corporate strategy. As R. Edward Freeman argues, stakeholders’ interests increasingly converge over time. This suggests a developmental process: If stakeholders’ interests align ever more closely with each other, then the stakeholders in question will gradually – and naturally – come together, forming alliances in the worst-case scenario. If the social momentum achieved by these cooperating actors grows proportionately, these actors may then be able to assert their interests successfully, for example through legislation. In most cases, this is the least desirable outcome, because it restricts the company’s room for maneuver. It follows that companies need to address stakeholders’ interests and integrate them into their business processes. If companies are not proactive in this way, they may find themselves compelled to act due to new state regulations. Over the medium term, management of stakeholders becomes management for stakeholders. This would probably represent the most radical shift imaginable for today’s managers.

Stakeholder management in companies has been implemented mainly in a descriptive manner until now; interest groups are, at best, informed about corporate plans. However, the potential to involve them in strategic discussion and decision-making processes goes much further. In the future, a more normative perspective and the associated concept of shareholder value will gravitate to the center of corporate activity – with the recognition that stakeholders are a constitutive element of business success. Their strategic and systematic integration will become one of the decisive factors in any such success.

The digitalization of communications is strengthening networks among stakeholders

The reasons for this lie in a coming of age and an increase in autonomy in those stakeholder groups that, until now, had been unable to properly articulate or assert their interests vis à vis companies and institutions.

New channels of communication have given rise to greater powers of interest assertion, which can hamper – or even prevent – the implementation of strategic decisions such as investments in infrastructural measures or bringing new products onto the market. Legitimate interests are no longer being articulated solely by opinion-leading stakeholders such as “the politicians,” “the media,” “the banks,” or “the NGOs,” but by local communities, parents, civic leaders, investors, associations, teachers, doctors, and ratings agencies. Alongside the so-called primary stakeholders, there are an increasing numbers of secondary and tertiary stakeholders who are putting forward clear positions and convincing cases.

Moreover, responsible, sustainable, and ethical corporate leadership is no longer generally regarded just as a social ideal but as a commercial necessity. Sustainability and improved efficiency, previously believed to be in conflict, are now recognised as joint prerequisites for competitive advantage.

Future importance of stakeholder management

The reason for the high importance attached to stakeholder management by small and medium-sized enterprises lies in the increasing pressure that stakeholder groups are now exerting on such firms. Whereas it was mostly big players who were under attack around the time of the millennium, today it is increasingly the so-called hidden champions – classic business-to-business companies – that are being closely monitored by critical stakeholder groups. The objects of this media attention are no longer only companies from the food production, financial, energy, and automobile sectors, but also include components suppliers, food retailers and delivery companies, raw materials suppliers, and mechanical engineering companies.

This trend is going to continue. Critical stakeholder groups are expanding their horizons beyond consumer and environmental concerns to take in the entire business supply chain. Whereas in the past, questionable product or contractual issues dominated the debate, today all the links in the corporate value-creation chain are scrutinized under ecological, ethical, and sustainability criteria with the aim of comprehensive risk- and sustainability management. It is in this spirit, too, that NGOs now publicly proclaim that they will no longer restrict their attacks to major companies but will deliberately include small companies and suppliers.

Graphic: Dr. Klaus Lintemeier/Dr. Lars Rademacher/Dr. Ansgar Thiessen

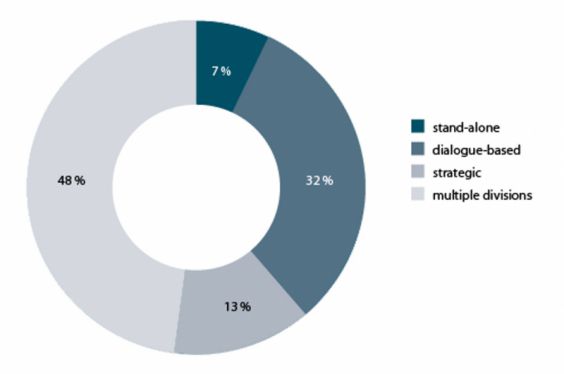

In the coming years, therefore, companies will have to work out for themselves the answer to the question of whether the organization of stakeholder management should be central or decentralized and how it should therefore relate to already established corporate divisions. The results enable a fundamental division into three possible categories.

Group One: Stakeholder management organized as autonomous division

This group is relatively small, comprising only 7 percent. The companies surveyed enable no conclusions to be drawn on whether the establishment of an autonomous division is dependent on the number of employees (e.g., predominantly in large companies), on the sector (e.g., predominantly in pharmaceutical companies), on turnover (e.g., predominantly in companies with a large turnover), or on the organizational location of stakeholder management (e.g., predominantly as a C-level function).

The reason for this lies in the fact that the professionalization of stakeholder management is only now slowly beginning. American companies with European headquarters in Germany, Austria, or Switzerland, for example, demonstrate a more frequent propensity to locate stakeholder management in an autonomous division. In international comparison, the management of stakeholder interests in the companies surveyed here is predominantly the responsibility of the communications division. American experience demonstrates that a targeted integration of process controls within a dedicated corporate division is crucial to the success of stakeholder management.

Group Two: Stakeholder management located in dialogue-based corporate functions.

In approximately one-third of companies, stakeholder management is organized in dialogue-based corporate functions such as corporate communications or public affairs/corporate affairs.

The reasons for this are mainly “historical.” Both corporate communications and public affairs/corporate affairs are responsible for communications tasks conducted by way of dialogue. However, the stakeholder approach is interpreted in the first instance only as an extension of acknowledged legitimate interest groups beyond the media, customers, employees, and capital markets. We demonstrate below that dialogue is understood as a channel for information and not as a form of consultation.

Group Three: Stakeholder management located in more strategic organizational units.

In this group, stakeholder management is accorded a greater priority within corporate leadership and thus acquires the status of a management function. It is explicitly not detached from other corporate divisions (“stand alone”), nor is it restricted to its purely communications elements (“dialogue-based”). Firms that organize their stakeholder management in this way incorporate a stakeholder perspective in their discussions and decision-making processes. Here, stakeholder management is integrated on the management level, and it is precisely there that its contribution is made.

Stakeholder management has a resource problem

One indicator of the significance of a corporate function is its financing, or the number of full-time staff posts assigned to it. Roughly 40 percent of the firms surveyed have created a full-time post for stakeholder management. A further 40 percent allocate between two and five posts to stakeholder management.

Firms with higher annual turnover tend to allocate greater resources to stakeholder management. The highest staffing numbers are to be found in affiliate companies (33%), strategic management holding companies (29%), and in autonomous corporate divisions (14%). The number of full-time posts allocated to stakeholder management in financial and intermediate holding companies is just as small as that in sales and distribution companies. The latter figure is particularly striking for Switzerland, where multinational companies with local sales and distribution subsidiaries are particularly well represented. Systematic stakeholder management is not carried out in the subsidiaries. The responsibility for this function usually remains with the group holding company located abroad.

Around 10 percent of those firms with only one full-time post have a turnover in excess of €5 billion (4.16 million Swiss Francs) and employ more than 10,000 workers. In these firms, stakeholder management is either part of a broader corporate function or is conceived as a temporary project.

All together, the number of full-time posts allocated to stakeholder management, at between one and five, is small in comparison with the number allocated to communications and public affairs divisions.

The increasing importance of stakeholder management has not yet had a substantial impact on staffing structures.

The management of stakeholder interests has only limited positive impact on the implementation of corporate plans

In 67 percent of the firms surveyed, stakeholder management is understood as relationship management, as a strategic tool providing a safeguard against corporate risks. In 64 percent of the firms surveyed, it is employed in the building and development of corporate reputations.

Stakeholder management therefore has its greatest significance as an essentially defensive risk-management measure (67%). Its claims of being a tool for corporate reputation-building are based, above all, on the understanding of stakeholder relations primarily operating through the media: Media and communications divisions often explain their roles in the firm with reference to their contributions to reputation management.

However, stakeholder management has its greatest impact as a strategic instrument for defending a corporation’s ability to maneuver freely. This is especially the case when all of the relevant stakeholders and opinion leaders are brought into a process at an early stage. Among those charged with this responsibility in companies, 36 percent see stakeholder management as playing a role in conflict management in cases where there is resistance from critical stakeholder groups. A failure to involve critics would lead to ignorance of relevant viewpoints and a misperception of influencing and campaigning capacities. This effectively also means that stakeholder management must, in the future, become an obligatory element of decision-making and planning processes (currently 37%).

10 theses on the stakeholder management of the future

In conclusion, we would like to put forward – as the quintessence of the findings of our study – the following 10 theses on the future development of stakeholder management. They are set out in more detail in the print version.

- The stakeholder approach goes well-beyond simple reputation management.

- The early integration of stakeholders optimizes corporate processes.

- Stakeholder management will become more closely aligned with the supply chain.

- The organization of stakeholder management will be professionalized, and interface problems will become more complex.

- Firms will provide more explanations and justifications for their decisions and plans.

- Firms will adapt the content of their mission statements to the stakeholder approach.

- Stakeholder management will move away from its focus on critical interest groups.

- Corporate communications will free itself from its obsession with the media.

- Internal stakeholder communications will step out of the shadow of external communications.

- There will be a convergence between normative and strategic issues in corporate governance.

The study “Stakeholder Integration” includes a foreword by R. Edward Freeman and a preface by Eberhard von Koerber. It was published by MHMK University Press and can be bought in Germany at bookshops or ordered directly from www.lintemeier-stakeholder.de.

Klaus Lintemeier is CEO, Partner, and Founder of the communications consultancy Lintemeier Stakeholder Relations, Munich/Vienna. He advises on strategic issues, stakeholder communications, and change management.

Dr. Lars Rademacher is Professor of Corporate Communications and Course Leader for media management at the MHMK in Munich. His research areas are CSR; compliance and reputation; strategic and leadership communications.

Dr. Ansgar Thiessen is Managing Director of Knobel Corporate Communications AG, Steinhausen, Switzerland. He advises family firms, medium-sized enterprises, and international holding companies in situations critical to their success and on strategic processes.

About Us // Privacy Policy // Copyright Information // Legal Disclaimer // Contact

Copyright © 2012-2018 macondo publishing GmbH. All rights reserved.

The CSR Academy is an independent learning platform of the macondo publishing group.