Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A Bridge to Breakthroughs

“Innovate or die” has become almost a mantra for companies in this era of rapid technological change and globalization. When we consider such conditions as extreme air pollution in Beijing, factory collapses in Bangladesh, drought in California, and deadly heat waves in India, the darker side of this foundational belief stands out in high relief. Yet we continue to settle for and cling to consumption-based business models that add to these global threats. Many large companies have survived and thrived for decades by selling high-calorie, sugary drinks or distributing apparel made by people working in extreme poverty for unfair wages in unsafe conditions.

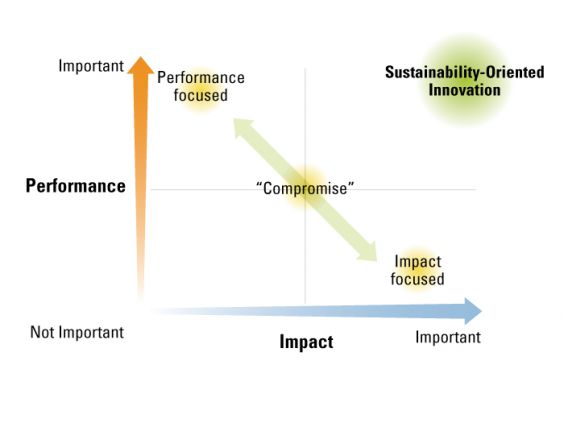

Overcoming these challenges and enabling societies to thrive on a planet with increasingly finite resources will take significant innovation. We call this sustainability-oriented innovation (SOI). SOI is about dispelling the notion of tradeoffs between what seem to be competing goals — performance versus impact, profit versus purpose, human wellbeing versus environmental protection. Our research suggests that when we no longer see these goals as competing, we create products, services, and business models that are holistic rather than fragmented. The potential for SOI exists within all firms. We just need to understand the barriers to unleashing it. Our research suggests that one critical barrier to achieving SOI is the “sustainability tradeoff” view of the world, a mental model that says having a positive social and environmental impact must exist as a tradeoff with more traditional business drivers.

Let’s look at Nike as an example of a company that discarded its tradeoff model. In the late 1990s, it started to develop an organizational commitment to environmentally responsible shoe design. One of its early forays into this work was the “Trash Talk” shoe, a shoe made from scraps of discarded material. The intended social value was to find a productive use for cutting-floor waste in the factories. Less waste meant using less energy, less water, and fewer chemicals.

But the shoe was a commercial failure. Customers did not find it aesthetically appealing, and Trash Talk did not have all the performance characteristics that Nike athletes had come to expect from their footwear. For Nike, succeeding with SOI meant holding firm to its commitments to both performance and impact. While Trash Talk had been a “compromise,” moving along the tradeoff line, they needed to push the envelope.

The Impact/Performance Frontier

After an extensive search and invention process, Nike took a very different approach from the one they had been using. On the impact dimension, they sought to achieve zero waste on the cutting room floor, a standard that far exceeded any they had set in the past. On the performance dimension, they sought to make shoes lighter and more breathable. By committing to achieving both performance and impact, Nike had let go of its either/or approach. The result was Flyknit, a new technology that involved weaving the upper portion of the shoe from a single thread. They had learned what artists have long understood — that constraint generates innovation. For Nike, holding impact and performance constraints simultaneously led them to an entirely new way of producing athletic footwear.

Nike Flyknit technology involves weaving the upper portion of a shoe from a single thread. It reduces the shoe’s overall environmental footprint and at the same time increases its athletic performance with lighter weight and flexibility.

By creating a new way to manufacture its popular running shoes, Flyknit produced what Nike CEO Mark Parker summed up as an innovation with “…the potential to change everything.” Flyknit is a mainstream product, marketed as a high-performance shoe. Its sales are projected to surpass $1B in 2016, which for a single shoe is an astounding accomplishment given Nike has an $18.3B total footwear business.

In our example, Flyknit hit the SOI sweet spot and tackled all three constraints simultaneously by creating customer value by increasing comfort and running performance; creating business value by cutting production time and costs, and addressing mainstream customer needs with significant market potential; creating system-wide environmental and social value by reducing landfill waste and reducing the need for labor-intensive, low wage work.

The Customer-Business-System constraints

We know that successful SOI doesn’t occur in isolation but through collaboration. Dutch startup DyeCoo Textile Systems B.V. completely revamped Nike’s textile dyeing by using an entirely waterless process called ColorDry, which reduced water demand by 100-150 liters of water (26-40 gallons), reduced dyeing time by 40% and energy use by 60%, and reduced the factory footprint needed for production by 25%. DyeCoo’s technology was a game-changer. While Nike Flyknit and DyeCoo ColorDry have both proven to be powerful technological innovations, SOI is not limited to cutting-edge technologies. It also has impact at the organizational, institutional and social levels.

Types of Sustainability-Oriented Innovation

Consider new intra-company “process” innovations like Buffer’s transparent salary bulletin and calculator, Tesla Motors’ “system infrastructure” changes like its international EV supercharging network, and Uber’s new “delivery and business model” innovation for car-sharing taxi alternative. These are all prime examples of the versatility of SOI across the organizational, institutional, and societal levels of innovation. They all work within different boundaries of change — from individuals to the inside of firms, firms to the inside of states, and states to the inside of society. In pursuing these bigger, more systemic solutions, SOI embraces a wide swath of commercial and civic stakeholders. Entrepreneurs, corporate intrapreneurs, policymakers, NGOs, investors, academics and active citizens all play a role in SOI success.

Embracing such diversity dispels the notion of single-player innovation and focuses instead on increasing opportunities for growth and scale through a multi-stakeholder approach. With this wider perspective and more diverse population of stakeholders, it becomes possible to tackle the big challenges more effectively and to be part of the solution that creates a positive future for business and society at large. In our subsequent blog posts, we explore the types of firms and strategies that can mesh with SOI, and the process of multi-stakeholder innovation.

Why Sustainability-Oriented Innovation Is Valuable in Every Context

Sustainability, sometimes under the banner of corporate social responsibility (CSR), used to be a specialty practice used by only a few companies, like Nike and Coca-Cola, to manage risks to their high-value brands.

But times have changed, and as we described in our first post, Nike is now using sustainability to drive the top line by enhancing product development and revenue growth with technologies like Flyknit. Startups like Liquiglide and its super-surfactant products, unicorns like Uber and its on-demand transportation service, and large systems integrators like Lockheed Martin with burgeoning renewable energy and energy storage systems are combining sustainability with revenue generation in various ways. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation (SOI) is the basic enabler of this trend.

Because SOI allows companies to push beyond their usual innovation boundaries and their typical business protocols, it is expanding the range of businesses that are practicing sustainability and finding new fuel for their innovation processes. It is also allowing them to reap the benefits of products and services that create social and environmental good.

The context and intent around SOI influences its final shape and form. Our research has identified three degrees of sustainability orientation: Sustainability-relevant, sustainability-informed, and sustainability-driven.

The most common form of SOI in the mainstream corporate world is sustainability-informed innovation (SII). The aim of SII is to meet a well-defined customer need using a design informed by sustainability considerations. Nike and its Flyknit technology discussed in our first post offer a good example of SII.

Many "green" brands and internal labels, such as Clorox Greenworks and Johnson & Johnson’s Earthward program, also fit this category. Some companies, like Patagonia, build their whole R&D portfolio around SII. Since its founding in the 1970s, Patagonia’s mission statement has evolved from "build the best product" to "use our business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis."

With this mission statement in mind, sustainability has become integral to Patagonia’s innovation process, which has resulted in products such as "synchilla" fleece made from recycled plastic bottles and the recent Yulex wetsuit — the first bio-material-derived wetsuit in the surfing industry.

The partnership between Patagonia and Yulex paired each firm’s core competencies in materials technology to enable the creation of the world’s first sustainable wetsuit. Their SOI was then shared with the rest of the surf industry, and now the same environmental technology can be found in almost all brands' premium wetsuits.

Nike Flyknit and Patagonia Yulex illustrate two benefits that companies reap through SII. The first is that sustainability constraints help drive a wider search for new materials, new processes, and new designs that can yield higher performance products. The second is that SII creates possibilities for differentiation among sustainability-minded customers. In this way, it manages risks and opportunities as customer preferences and regulations change.

Sustainability-Driven Innovation (SDI) is another kind of SOI that innovates with the specific goal of solving a public problem. An example of technology-based innovation would be renewable energy companies like SunPower, which are developing high-efficiency solar photovoltaic panels to mitigate the air and climate pollution associated with fossil fuels.

Other enterprises, like Sanergy, achieve SDI through business-model innovation. Sanergy is an MIT spinoff established to solve sanitation problems in the developing world. Knowing that nearly 8 million people in Kenyan slums lacked access to a proper sanitation, the Sanergy team used $25,000 from the MIT Public Service Center to test their solution. They installed two toilet stations and franchised them out to local entrepreneurs, who maintained them and charged for use. Sanergy safely collected the waste and converted it into fertilizer that could be sold to farmers. The pilot was so successful that in 2011 the team formed a for-profit and non-profit business to continue its work. The for-profit arm developed and sold the toilet stations and waste fertilizer. The non-profit arm supported the franchisees and infrastructure with training and services.

Sanergy’s results are impressive and include:

- installation of 734 toilets

- 33,000 daily uses

- removal and treatment of 6,028 metric tons of waste

- creation of 763 jobs

In addition, local entrepreneurs, 35%–40% of whom are women, are making a profit of at least $1,000 per year; organic fertilizer made from the waste sells for 30% less than inorganic alternatives; and local school attendance increased 20% after schools purchased toilets, which gave parents more confidence to send their children to class.

The third form of SOI, sustainability-relevant innovation (SRI), is the most broadly applicable but the least discussed. SRI is about discovering and leveraging hidden sustainability benefits after innovation. Zipcar and the car-sharing revolution are a prime example. The practice dates back to the late 1980s in Europe with the rise of programs like Mobility Switzerland and StattAuto Berlin. Convenience and cost savings were the original value drivers of the innovation. The success of these programs in providing superior benefits over owning a car led to wide adoption in the United States and Europe. In addition, membership exploded once Internet technology made it possible to streamline business operations.

Zipcar rode this wave after debuting in Boston in June 2000, and its leadership quickly realized that this new business model had tangible sustainability benefits as well. Entering into public-private partnerships with cities like Baltimore made Zipcar aware that their business was encouraging people to sell their cars, avoid buying new ones, take fewer trips, drive fewer miles per trip, walk and bike more, and take public transit more often.

Another positive by-product of SRI for Zipcar was the unanticipated recruitment of allies for its business. Cities and universities came to see it as an eco-friendly alternative to car ownership, with the added benefit of fewer regulatory barriers and lower parking prices.

These behavioral changes all entailed real social and environmental benefits. Although more research is needed around their quantification, better air quality, less traffic congestion, and more physical activity are highly likely. Zipcar stumbled upon these sustainability benefits as a free and positive side effect of its business-model innovation and made it possible for people to drive within a new sustainability-oriented context. The result of Zipcar’s SRI activities was nothing short of industry shaking.

SRI can also grease the wheels for SII and SDI projects. Consider GE’s "Ecomagination" strategy. When it began, GE focused on identifying the environmental benefits of their existing products, such as more energy efficient appliances and engines. By marketing these benefits to customers, employees, investors, and other stakeholders, GE established broader legitimacy of an SOI approach. From that foundation, GE was able to undertake SII and SDI projects. EcoSwitch — a tea kettle, slow cooker, hot plate, and blender combined into one energy efficient package — is an SII product, and Open Innovation was an SDI project that called for innovators to solve water scarcity and energy challenges in international communities struggling with those issues.

Although one form of SOI may have significantly greater scale or impact than another, all three are beneficial. The sum reduction in GHG emissions from car-sharing (SRI, Zipcar) and the GHG emission reductions achieved by replacing petroleum-based neoprene with e-fiber in wetsuits (SII, Patagonia) are both beneficial, even though the former clearly will have a larger-scale impact than the latter.

Each of these three SOI variations will have its own area of impact. SIIs will tend to include mainstream consumption channels and foster shifts in industry impact. SDIs will tend to push the envelope and be very specific in focus. And SRIs impact will be in discovering and leveraging hidden sustainability benefits after innovation.

Whether technological, organizational, institutional, or social innovation, SOI practitioners will benefit by recognizing the need for an ecosystem of SOI that will accommodate the entire spectrum of impact.

Jason Jay is a Senior Lecturer and Director of the Sustainability Initiative at MIT Sloan. Sergio Gonzalez is a graduate student in the MIT Technology and Policy Program. Marine Gerard is a 2014 graduate of the MIT Sloan School of Management currently working as an associate at the Boston Consulting Group.

The article was originally published in the Sloan Management Review.

Resources

What is Sustainability-oriented Innovation (SOI)?

Learn what Sustainability-oriented Innovation (SOI) means to professors, directors and students at MIT.

Lecture: MIT Sloan Management Review

Why do companies that embrace sustainability seem to outperform those who don't? What makes these companies different? Is this an advantage your company can gain? Moderated by Michael S. Hopkins, Editor-in-Chief of MIT Sloan Management Review, panel guests Peter M. Senge, Peter Graf and Knut Haanaes discusses the implications of MIT Sloan Management Review's recent global study.

About Us // Privacy Policy // Copyright Information // Legal Disclaimer // Contact

Copyright © 2012-2018 macondo publishing GmbH. All rights reserved.

The CSR Academy is an independent learning platform of the macondo publishing group.